When Winter Becomes an Asset: Global Cities Reassess the Economics of Ice and Snow

This article contains AI assisted creative content

Harbin, a city long defined by extreme cold, is increasingly being examined not for its climate, but for how it has converted that constraint into a scalable economic system.

At the Global Mayors Dialogue held in early January, municipal leaders from winter cities across Canada, Finland, and the Republic of Korea gathered in Harbin to exchange views on the emerging ice and snow economy—a sector that now spans tourism, equipment manufacturing, sports infrastructure, and cold-climate technologies.

For visiting delegations, the relevance went beyond cultural spectacle. Harbin Ice and Snow World, the largest ice-and-snow theme park globally, and the city's long-running Ice and Snow Festival were repeatedly cited as examples of how seasonal assets can be industrialised rather than merely celebrated. Edmonton's mayor, representing a city with comparable winter conditions, described the scale and organisation of Harbin's winter economy as “beyond conventional expectations” for cold-region tourism.

Officials from Bucheon and Rovaniemi—both long-term sister cities of Harbin—framed the discussion in more structural terms. In their view, winter festivals function not as standalone events, but as anchors for broader value chains: hospitality, transport, creative industries, equipment manufacturing, and international branding. Decades of municipal cooperation have already produced tangible outcomes in trade, education, and tourism, suggesting that cold-climate cities may share more than symbolic ties.

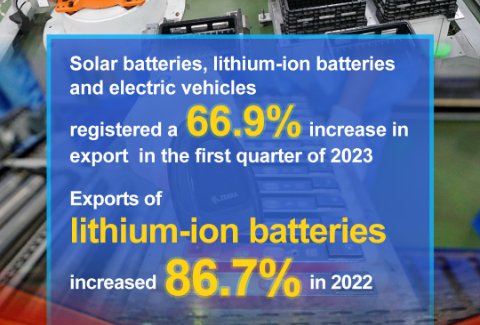

The dialogue coincided with Harbin’s first International Ice and Snow Expo, where industrial-grade snow-removal systems, snowmobiles, and carbon-fiber ski equipment were showcased. The exhibition underscored a less visible dimension of the ice and snow economy: capital-intensive hardware and technology, increasingly relevant as cities confront both climate volatility and infrastructure resilience.

From a macro perspective, the numbers are material. Harbin’s ice and snow-related output exceeded RMB 160 billion (approximately USD 23 billion) in 2024—around one-sixth of China’s national total for the sector. Nationally, China’s ice and snow economy surpassed RMB 1 trillion in 2025, supported by more than 14,000 tourism-related enterprises, according to the China Tourism Academy. Policymakers expect the sector to expand to RMB 1.2 trillion by 2027 and RMB 1.5 trillion by 2030, positioning it as a long-term driver of consumption rather than a cyclical niche.

What emerged from the dialogue was not a narrative of celebration, but of comparative advantage. For winter cities, the question is no longer how to endure cold seasons, but how to monetise them—through technology, urban planning, and international cooperation. Harbin’s experience offers one model, but the broader implication is that climate constraints, if systematically managed, can evolve into durable economic assets.

In that sense, ice and snow are no longer merely weather conditions. They are becoming balance-sheet variables.

First, please LoginComment After ~