Dr Kelvin Wong on Succession as the Missing Link in Modern Governance

This article contains AI assisted creative content

At the Hong Kong Chartered Governance Institute's Annual Celebration Reception in January 2026, Dr Kelvin Wong, Chairman and recipient of the HKCGI Prize Award, delivered a message that resonated strongly with governance professionals: the effectiveness of governance frameworks in the coming decade will depend less on new rules and more on how organisations manage succession as a core governance process.

Speaking against a backdrop of demographic ageing, technological disruption and market volatility, Wong argued that many governance failures are not caused by weak frameworks, but by a lack of leadership continuity. In his view, succession remains one of the most underestimated structural risks in corporate governance.

From Written Frameworks to Lived Governance

Wong observed that struggling organisations often have well-documented governance policies. The real problem, he noted, lies in the gap between governance “on paper” and governance in practice. That gap emerges when leadership capability is not deliberately renewed.

Rather than treating succession as a one-off appointment decision, Wong framed it as a long-term stewardship mechanismthat spans boards, committees and senior management. In this sense, succession is not an HR exercise, but a governance discipline that determines whether institutional memory, strategic intent and values survive leadership transitions.

A recurring theme in his remarks was that “governance depends on people before it depends on policies.”Without sustained leadership capacity, even the most sophisticated frameworks lose their effectiveness.

The Economic Cost of Deferred Succession

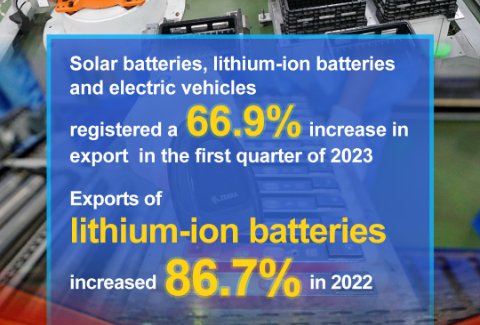

Wong underscored the material consequences of weak succession planning. Poorly managed leadership transitions, he noted, are associated with nearly US$1 trillion in annual market value loss among S&P 1500 companies, alongside erosion of stakeholder trust and organisational performance.

These risks are amplified in today's environment, where ageing leadership cohorts intersect with rapid innovation cycles and increasing reliance on technologies such as artificial intelligence. According to Wong, organisations that delay succession planning often find themselves forced into disruptive, last-minute leadership changes precisely when stability is most needed.

Selecting Leaders for the Future Context

A key contribution of Wong’s analysis was his emphasis on context-driven succession. Future leaders, he suggested, should be selected not merely for past performance, but for their alignment with where the organisation is heading.

He highlighted three attributes as critical:

Strategic vision to anchor long-term positioning;

Adaptability to navigate uncertainty without compromising governance standards;

Stakeholder influence to sustain trust across investors, regulators and employees.

Importantly, Wong stressed that different roles require different succession profiles. Compliance and operational leadership depend on continuity and institutional knowledge, while innovation-driven roles require agility and forward-looking capabilities. Effective succession, in his words, is about “matching leadership to future demand, not historical comfort.”

Demographics as a Governance Signal

Using Hong Kong as an example, Wong pointed to the rising average age of board chairs, directors and CEOs among large listed companies. While experience remains a strength, he cautioned that concentrated leadership transitions could pose governance risks if not anticipated and managed systematically.

In this context, succession planning becomes a form of risk management — one that addresses demographic reality rather than reacting to it.

Re-energising Governance: Three Practical Pathways

Wong outlined three practical directions for organisations seeking to strengthen governance through succession:

First, embed succession into formal governance structures, including board charters, evaluations and remuneration discussions, making leadership continuity a matter of oversight rather than discretion.

Second, institutionalise mentorship and knowledge transfer, ensuring that culture, judgement and stakeholder relationships are passed on deliberately rather than lost during transitions.

Third, treat continuous learning as a governance obligation, recognising that leadership capability must evolve alongside markets and stakeholder expectations.

Governance as a Self-Renewing System

Wong concluded by framing succession as the mechanism through which governance renews itself. When embedded properly, succession creates a virtuous cycle: strong governance develops capable leaders, capable leaders reinforce governance quality, and sustained performance strengthens market confidence.

As he implied, governance without succession is structurally incomplete. In an era defined by transition, leadership continuity is no longer a soft issue — it is a determinant of institutional resilience and long-term value creation.

First, please LoginComment After ~